In this blog post I share a longstanding interest of mine, the uses and meanings of photography within humanitarian contexts. Within humanitarian situations visual representations whether through photography, posters, film, or drawings have played a central role in shaping how suffering is made visible. From emergency relief campaigns to global health interventions, such images have garnered humanitarian responses, rallied public attention, and evoked compassion. But they also raise important questions: How do audiences receive these images and how do we understand them in various archival contexts?

The Humanitarian Archive at the University of Manchester holds a rich collection of visual materials including posters, slides, relief campaign images, stamps and artwork that were used across diverse contexts and histories. These come from different people and organisations involved in aid and global health revealing a long and complex history of representing need, suffering, and care. The variety of representations in this collection tells us that humanitarian photography is more than a genre of photography. It eludes definition but has relied on a subset of recurring images and tropes, scenes of urgency, helplessness, and vulnerability. These images are powerful, but as many have pointed out they have framed people’s lives into one-dimensional stories of need. This is where ethical questions come in. How should we look at suffering? What is our role as viewers? What responsibilities do photographers and aid groups have when they create and share these images?

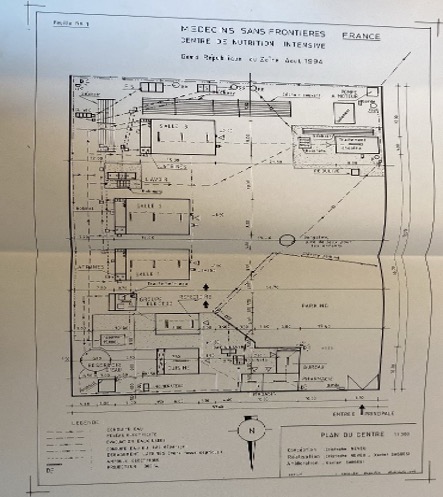

In May I had the opportunity to research the Archives from Médecins Sans Frontières (MSF) in Paris and the drawing below (Figure 1) shows the planned layout of a nutrition centre in Goma, Zaire (now the Democratic Republic of Congo), during the 1994 Rwandan refugee crisis. Everything is clearly marked out and highly organised; including structures demarcated for patients, cholera treatment, incineration, pharmacy and water points.

Figure 1 Plan for a Nutrition Centre, Goma, Zaire (1994)

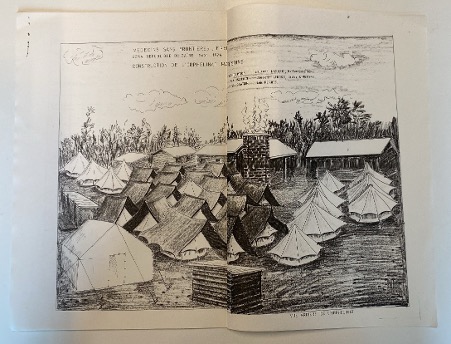

In contrast, a hand-drawn sketch (Figure 2) of an orphanage from the same period points us to a different dimension of a humanitarian crisis, the realities of the genocide in Rwanda such as loss. We see tents, smoke rising from a chimney, lush vegetation and clouds in the sky that render a softer and less distanced reading. Tom Scott-Smith argues in his book Fragments of Home, that these kinds of temporary shelters aren’t just practical, they reflect specific ideas about control, order, and what kind of life is possible in a crisis. Both drawings, one technical and precise, the other evocative share something interesting – the absence of the people they were made for. We do not see how people lived within these spaces and navigated difficult situations.

Figure 2 Sketch of Orphanage Grounds, Goma, Zaire (1994)

At DHM we are also interested in how visual representations have evolved in a world of rapid technological change. In my upcoming work I will be exploring how techniques of ultrasound and AI-based diagnostics are currently being used in a cervical cancer intervention are reshaping the visual field of humanitarian medicine and transforming how we see, diagnose, and define care.

In this short writing, I hope I have introduced how visual sources such as photographs, architectural plans, or AI images are never just representations. They shape how we understand crises, how responses are designed and sometimes how actors imagine humanitarianism. In this current moment saturated by apps and algorithms we need to pay attention to what new ways of seeing are emerging and ask: who benefits? I am interested in learning how others think about images in their work and how communities visualise care.

Images courtesy of MSF archives Paris. Box 6 RDC (Zaire) 1994. Bukavu/ Goma